Medical Residents' Perspectives on Palliative Medicine

Cynthia D. Lamon, Ed.D., A. T. Still University and Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences

Introduction

Palliative care is vital to health care because as the population ages and life-saving treatment and medication options increase the need for palliative care services will also continue to increase. However, education and training for most medical students and residents is inadequate to meet current palliative care needs1. Additionally, there is no uniform/universal curriculum offered nor a required number of hours for palliative medical education, nor mandatory clinical rotations or tracks for palliative care training in either osteopathic or allopathic medical schools2. Therefore, as per accrediting body curriculum requirements, medical schools are integrating palliative medicine education into core courses for the first two years of undergraduate medical school3; however, there is a substantial amount of evidence that this education and training does not sufficiently prepare medical students to care for dying patients4. This lack of preparedness affects not only the patient and the patient's family members, but also the resident and his or her ability to provide best-practice palliative care. Moreover, non-specialty-trained providers, such as primary care and internal medicine physicians, will be the most likely health care professionals to deal directly with the consequences of this gap5. This qualitative study was developed to explore medical residents' perspectives on palliative medicine training during residency. The research was grounded in Kolcaba's Comfort Theory, which has served as the foundational theory for research and practice for hospice care and palliative medicine over the past two decades6.

Methods

A qualitative case study approach was used to identify and examine gaps, and subsequently, opportunities for training osteopathic medical residents in palliative medicine during primary care and internal medicine clinical residencies in a large, Southern osteopathic medical school. Over 200 residents who were working or had worked recently in the medical school's outpatient clinics and/or hospitals were eligible for recruitment. To reach transferable results for a larger population sufficient sample size to reach saturation was necessary and dependent on several factors, including the quality of the data collected, scope of the study, nature of the study, and the amount of information deemed useful from each participant.

After IRB approvals and email recruitment, seven residents volunteered, and the researcher conducted one-on-one, semi-structured interviews. These were conducted in a safe and private area, audio recorded, and then transcribed data were coded and analyzed using both inductive and deductive, open coding techniques to facilitate thematic analysis. A constant comparison approach was used to develop salient themes and the process continued until theoretical saturation had been reached.

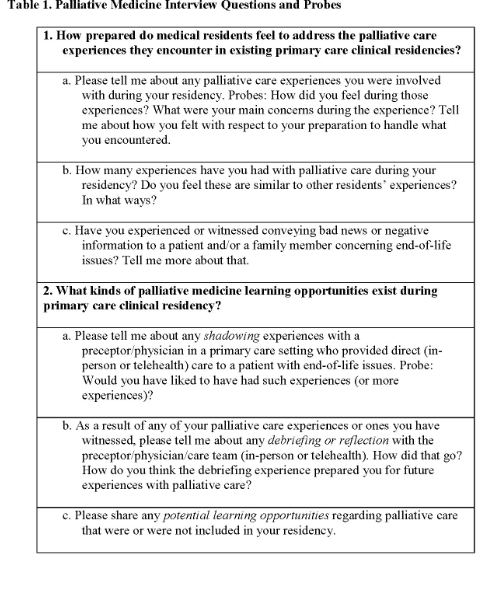

Six key interview questions (Table 1) were developed and based on the following two research questions:

• How prepared do medical residents feel to address the palliative care experiences they encounter in existing primary care clinical residencies?

• What kinds of palliative medicine learning opportunities exist during primary care clinical residency?

Results

The seven study participants were classified using gender, area of specialty, and year of residency (Table 2).

All study participants reported having palliative care and/or end-of-life experiences with patients during their residencies with differences in frequency between specialties (Table 3). The specialty areas also provided insight into the preparedness of each individual.

All study participants reported feeling more prepared due to hands-on encounters from early residency through each year of their continued residency. They also reported gaining confidence in skills due to experiential encounters specific to rotations in intensive care units in hospitals. Four of the residents reported bringing life experiences with them in order to know how to have difficult conversations with patients and their families.

Residents reported time constraints for reflection and debriefing exercises, as well as general stress levels of residency life. The participants reported hands-on experiences, shadowing and being mentored by other residents and attending physicians as the most effective and long-lasting learning methods; whereas simulations and listening to stories related to end-of-life care were not as effective nor long-lasting.

Table 4 shows a list of perceived gaps in medical education and residency training that was provided by each study participant.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify and examine the gaps and opportunities for training osteopathic medical residents in palliative medicine during clinical residency from the resident perspective by examining the kinds of palliative medicine experiences residents report and how prepared they feel to address them. A secondary topic of investigation was to discover what kinds of palliative medicine learning opportunities might exist during clinical residencies.

The level of preparedness for each resident varied by gender, specialty, and year of residency. The findings concerning gender were unique as previous research into education and training of palliative medicine for medical residents has not focused on these differences, although specialty area has been examined previously7.

All residents reported benefits and opportunities from shadowing more experienced physicians. Additionally, those residents who had opportunities for debriefing and reflection reported feeling less emotional toll from the loss of a patient.

An unexpected finding related to medical residents' remarks about the culture of medicine and regarding unspoken expectations surrounding death and dying. The remarks focused on the purpose of a physician's role and how they are trained to cure disease, save lives, and have all the answers, often taking on the leadership role in each situation. The culture of medicine has been described as a hidden curriculum8 that often shapes medical students' perceptions during training. Students described a hierarchy of medicine relating to their position within the system as guiding their actions. This included knowing when to speak and not to speak, as well as observing good and bad behaviors exhibited by physician role models. This long-standing culture may have a direct impact on the education and training of medical residents in preparation for caring for patients who are in the dying process as it is in direct opposition to most of their training.

Lastly, the study sample size was small and derived from one osteopathic medical college, which could pose as a limitation. Therefore, the addition of more research subjects, and/or perhaps including other osteopathic medical schools, would satisfy this limitation.

References

1. Van Aalst-Cohen ES, Riggs R, Byock IR. Palliative care in medical school curricula: A survey of United States medical schools. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(9):1200- 1202. doi:10.1089/jpm.2008.0118

2. Chiu N, Cheon P, Lutz S, et al. Inadequacy of Palliative Training in the Medical School Curriculum. Journal of Cancer Education. 2015;30(4):749-753. doi:10.1007/s13187-014- 0762-3

3. Radwany SM, Stovsky EJ, Frate DM, et al. A 4-year integrated curriculum in palliative care for medical undergraduates. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2011;28(8):528-535. doi:10.1177/1049909111406526

4. Smith GM, Schaefer KG. Missed opportunities to train medical students in generalist palliative care during core clerkships. Journal of palliative medicine. 2014;17(12):1344- 1347. doi:10.1089/jpm.2014.0107

5. Edwards A, Nam S. Palliative Care Exposure in Internal Medicine Residency Education: A Survey of ACGME Internal Medicine Program Directors. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2018;35(1):41-44. doi:10.1177/1049909116687986

6. Kolcaba KY. A theory of holistic comfort for nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;19(6):1178-1184. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01202.x

7. Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD. The status of medical education in end-of-life care: A national report. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18(9):685-695. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21215.x

8. Bandini J, Mitchell C, Epstein-Peterson ZD, et al. Student and Faculty Reflections of the Hidden Curriculum: How Does the Hidden Curriculum Shape Students' Medical Training and Professionalization? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2017;34(1):57-63. doi:10.1177/1049909115616359