Biliary Tree of Knowledge: Assessing Cholecystitis Google Searches

Cole R. Phelps, BS, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Office of Medical Student Research, Tulsa, OK, USA

Jared Van Vleet, BS, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Office of Medical Student Research, Tulsa, OK, USA

Samuel Shepard, DO, Kettering Health Network, Research Fellowship, Dayton, OH, USA

Griffin Hughes, BS, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Office of Medical Student Research, Tulsa, OK, USA

Ike Potter, DO, Oklahoma State University Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Tulsa, OK, USA

Ali Sharp, DO, Oklahoma State University Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Tulsa, OK, USA

Brian Diener, DO, Oklahoma State University Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Tulsa, OK, USA

M. Vassar, PhD, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tulsa, OK, USA

Corresponding Author: Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences

Address: 1111 W 17th St., Tulsa, OK 74107, United States.

Email: cole.phelps@okstate.edu

Phone: (918) 582-1972

Conflicts of Interest: No financial or other sources of support were provided during the development of this protocol. Matt Vassar reports grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Office of Research Integrity, and Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology, all outside the present work.

Funding: None.

Meeting Presentation: American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2023, Scientific Forum, Quick-Shot Oral Presentation, October 25, 2023

Abstract

Background:

Cholecystitis is a common form of upper abdominal pain. With its high prevalence and the various non-surgical and surgical treatment options, we believe patients are searching the internet for questions pertinent to cholecystitis. No investigation has ever been completed into cholecystitis Google searches; therefore we sought to classify these questions as well as assess their levels of quality and transparency using Google’s Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs).

Methods:

We searched Google using search terms involving cholecystitis treatment. The FAQs were classified by the Rothwell Classification schema and each source was categorized. Transparency and quality of the sources' information were evaluated with the Journal of the American Medical Association’s (JAMA) Benchmark tool and Brief DISCERN.

Results:

Our Google search returned 325 unique FAQs after removing duplicates and unrelated FAQs. Most of the questions pertained to surgical treatment (190/325, 58.5%), followed by disease process (79/325, 24.3%), and then non-surgical treatment (56/325, 17.2%). Medical practices accounted for the highest amount of FAQs unable to meet the JAMA benchmark (107/146, 73%). The one-way analysis of variance revealed a significant difference in median quality of Brief DISCERN scores among the 5 source types (H(4) = 49.89, P<0.001) with media outlets (10/30) and medical practices (12/30) scoring the lowest compared to academic sources which scored highest (21/30).

Conclusions:

Medical practices are the most frequent source Google recommends for FAQs but deliver the lowest quality and transparency. To increase the quality and transparency of online information regarding cholecystitis treatment, online sources should strive to include the date, author, and references for online information.

Keywords: Cholecystitis, Quality, Transparency, Rothwell Classification, JAMA Benchmark, Brief DISCERN

Abbreviations:

FAQ- Frequently Asked Questions

JAMA- Journal of the American Medical Association

PAA- People Also Ask

ANOVA- Analysis of Variance

DISCERN*- To clarify and avoid confusion, DISCERN is a title and not an abbreviation.

Introduction

Cholecystitis accounts for anywhere between 3-10% of all patients with abdominal pain and up to 200,000 people a year in the U.S. suffer from it.1–5 Non-surgical treatment options include analgesics or opioids for pain management and broad-spectrum antibiotics.6 Surgical treatment options are warranted for patients who either need emergency cholecystectomy or are at initial hospitalization for cholecystitis.6 The definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis, in a good surgical candidate, is a cholecystectomy when symptoms can no longer be managed conservatively.6,7

With increasing access and availability to the Internet, it should be no surprise that there are more and more patients searching the Internet to support their medical decision-making. 8 A significant portion of these individuals proceed to self-diagnose based on the information they find online when looking up their symptoms before reaching out to healthcare experts.Sup>8–10 Studies have proven this trend in orthopaedics and gastroenterology, however, no such trend has been studied in hepato-biliary diseases, especially in cholecystitis. 9,11–13 Due to the high prevalence of cholecystitis in patients with abdominal pain, we believe patients are turning to the Internet for treatment options for cholecystitis. Google’s search engine feature “People Also Ask” (PAA) continuously provides questions to one’s original searched question in a waterfall fashion.14 This creates an opportunity to leverage public questions related to cholecystitis. It has been shown in orthopaedic research that this feature can be used for search trend characterization of frequently asked questions (FAQ).15,16 No study thus far has applied this data characterization to cholecystitis.

Our aim is to characterize the FAQs regarding cholecystitis treatments, categorize the sources that answer those FAQs, and assess each source for its quality and transparency. Physicians must be made aware of the recurrent questions about cholecystitis and the content of which patients are displayed to guarantee they understand the benefits and risks of cholecystitis treatment.

Methods

Background

This study was conducted in accordance with a previously written protocol publicly available via Open Science Framework.17 The methodology in this current study has been modified and built upon previous works that examined FAQs relating to treatments for carpal tunnel, the COVID-19 vaccine, osteopathic medicine, and hallux valgus.18–21

Systematic Search

On January 23, 2023, we searched Google for four separate terms: “Cholecystitis Treatment”, “Cholecystectomy”, “Gallbladder Treatment” and “Gallbladder Removal Surgery.”22 These terms were chosen to collect the most expected inquiries related to treatment or surgeries for cholecystitis. We used the free Chrome extension SEO Minion to search and download the FAQs and answer links for each inquiry. 23 Previous studies have suggested using a minimum of 50-150 sources and we chose to use a minimum of 200.15,20 Each FAQ was screened for relevance on January 23, 2023. Our Google search returned 325 unique FAQs after removing duplicates and unrelated FAQs. All videos, paywall-restricted sites, and uploaded document returns were excluded.

Data Extraction

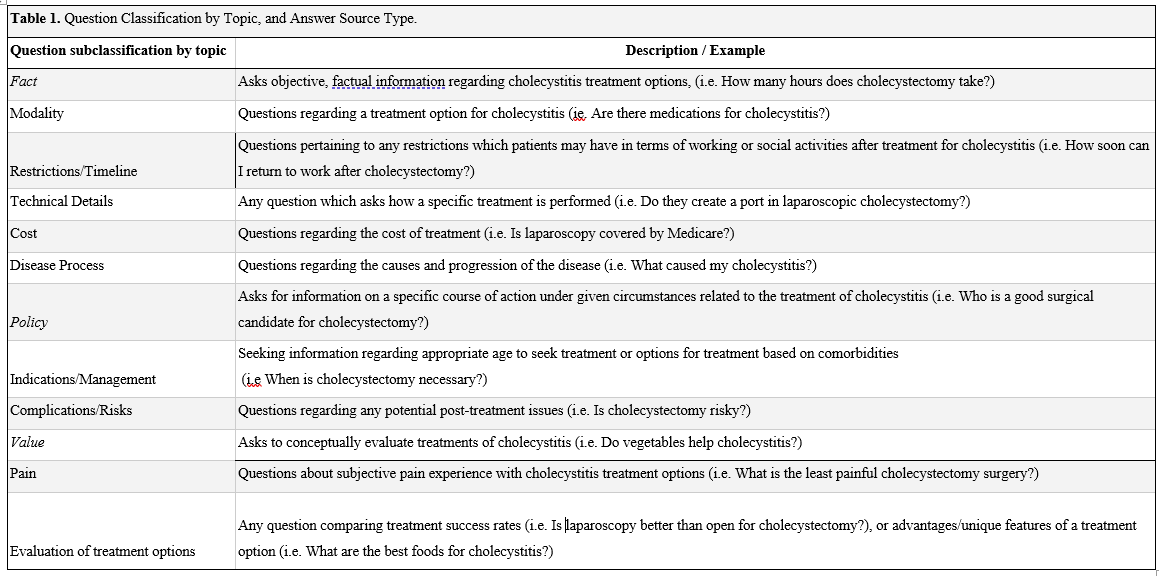

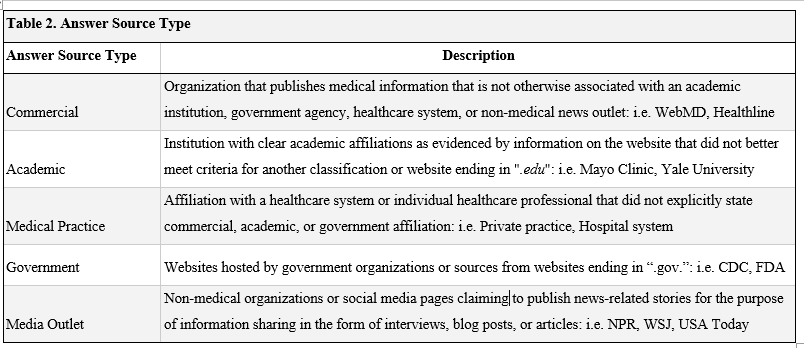

In a masked duplicated process, using a Google Form, JV and CP recorded each FAQ and their linked sources. Source types were categorized as either Academic, Commercial, Government, Media Outlet and Medical Practice according to previously established studies.20,24 Bearing methodology modified from published literature,15,20,25 FAQs were classified according to Rothwell’s Classification of Questions 26 indicating them as either Fact, Policy, or Value questions. Fact questions were subcategorized into 5 groups: Restrictions/Timeline, Technical Details, Cost, Modality, and Disease Process. Policy questions were subcategorized into 2 groups: Indications/Management and Complications/Risks. Value questions were subcategorized into 2 groups: Pain and Evaluation of Treatment/Surgery. Refer to Table 1. for Question Classification and to Table 2. for Answer Source Type definitions. Both the JAMA benchmark criteria and the Brief DISCERN tool were applied in a masked duplicate fashion for each source, and author GH resolved any discrepancies.

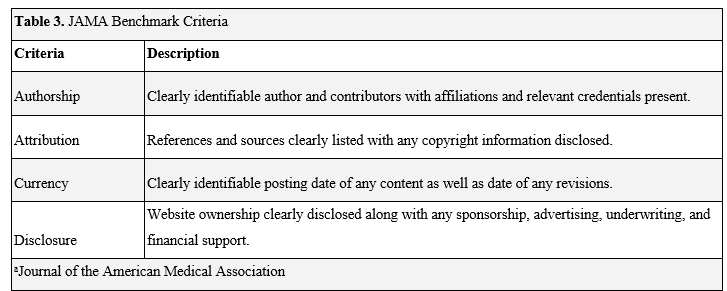

Information Transparency

Each source was assessed using the Journal of the American Medical Association’s (JAMA) Benchmark Criteria. Multiple studies have utilized the JAMA Benchmark to effectively partition online information for basal aspects of information transparency.15,16,20,27–30 The items measured to determine transparency were: authorship, attribution, currency, and disclosure. Sources meeting 3 criteria were considered to have high transparency, whereas any sources that were less than 3 criteria had low transparency. Refer to Table 3 for JAMA Benchmark Criteria definitions.

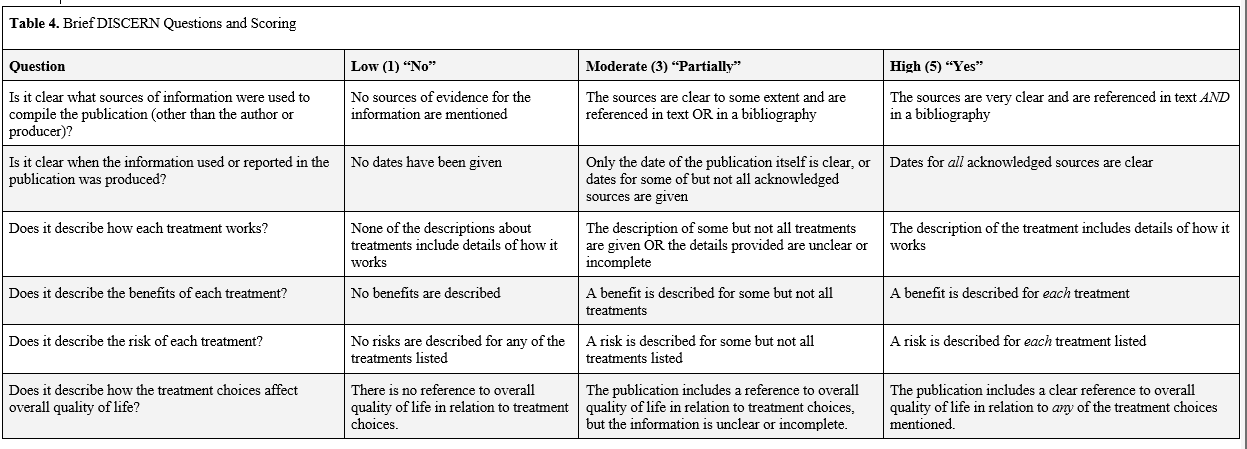

Information Quality

Each source was also assessed using the Brief DISCERN information quality assessment tool. DISCERN has been previously used to assess the quality of internet sources in various medical fields.20,31–33 Khazaal et al34 developed a 6-item version titled Brief DISCERN that has comparable reliability as well as maintains the advantages of the original tool in a simple layout. This justified our use of the Brief DISCERN quality assessment tool as used in other studies. 20,35,36 Each of the 6 questions can be scored from 1=No, 2/4=Partially, and 5=Yes for a maximum of 30. For this study, we considered all partial answers as a 3 to increase accuracy and precision for the partial category. We determined an aggregate score of 16 or greater to be of good quality as established by previous recommendations. 34 For specific details of the 6 questions see Table 4.

Analyses

Frequencies and percentages were reported for each type of FAQ. The Chi-Square Test of Independence was used to determine associations between JAMA Benchmark Criteria and source type. Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum was used to determine whether median Brief DISCERN scores significantly differed by source type. Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test was done post-hoc to determine the significance of DISCERN completion between source types. Statistical significance was set at P <.001. Statistical analysis was calculated in R (version 4.2.1).

Results

Search Return

A total of 1844 FAQs came from combining all four search terms: 380 from searching “Cholecystitis Treatment,” 620 from searching “Cholecystectomy,” 590 from searching “Gallbladder Treatment,” and 254 from searching “Gallbladder Removal Surgery.” After removing duplicates, there were 827 unique FAQs. Of these, 502 were removed because they either did not pertain to cholecystitis treatments or surgeries, were a link to a video resource, were restricted behind a paywall, or were a form of uploaded documents, resulting in a final count of 325 FAQs.

Question Classification

Of all the FAQs in our data sample, the majority pertained to surgical treatment (190/325, 58.5%), followed by disease process (79/325, 24.3%), and non-surgical treatment (56/325, 17.2%).

Using Rothwell’s Classification of Questions for cholecystitis FAQs, 218(67.1%) were fact-based questions, 64 (19.7%) were policy-based questions, and 43 (13.2%) were value-based questions. Of the 218 fact-based questions, the most frequent topic was Restrictions/Timeline (91/218, 41.7%), followed by Disease Process (61/218, 28.0%), Technical Details (35/218, 16%), Modality (31/218, 14.2%) and Cost (0/218, 0%). Of the 64 policy-based questions, the most frequent were Indications (33/64, 51.5%) followed by Complications (31/64, 48.4%). Of the 43 value-based questions, the most frequent were Evaluation (28/43, 65.1%) followed by Pain (15/43, 34.9%).

Answer Sources

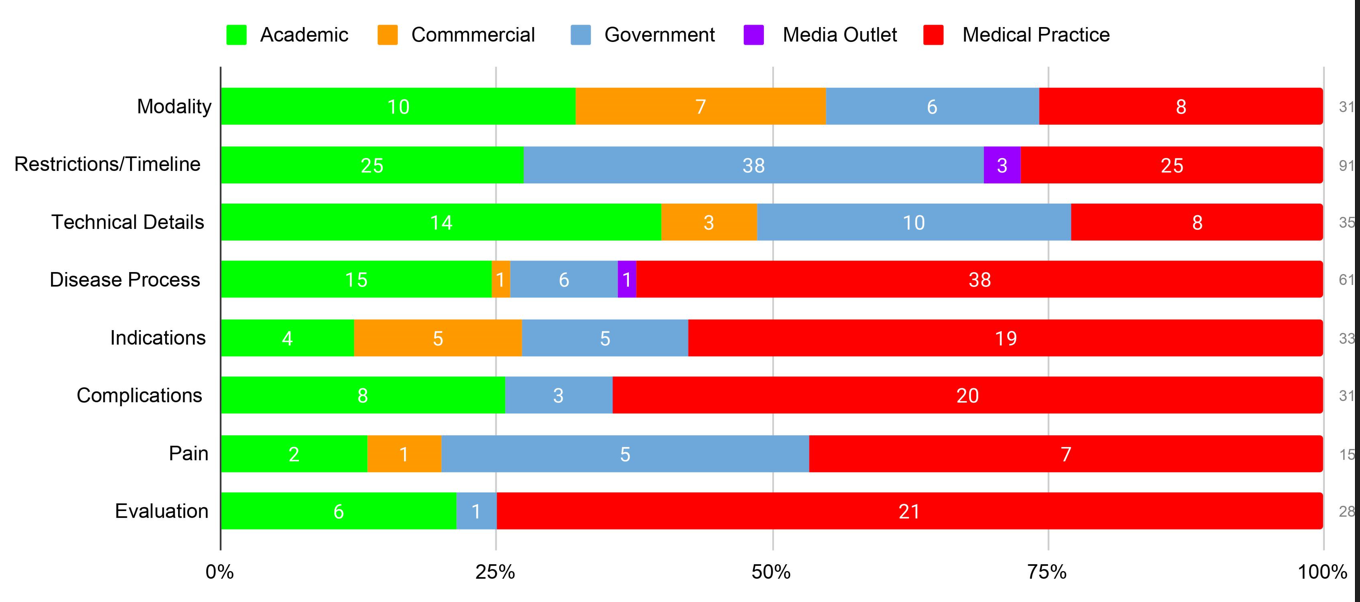

The most identified source within our sample was Medical Practices (146/325, 44.9%) followed by Academic (84/325, 25.8%), Government (74/325, 22.8%), Commercial (17/325, 5.2%), and Media Outlets (4/325, 1.2%). Medical Practices were also responsible for answering the most FAQs on individual topics such as Disease Process (38/61, 62.3%) and Evaluation (21/28, 75%). See Figure 1. for a breakdown of answer sources.

Figure 1. Question Subclassification by Source Type.

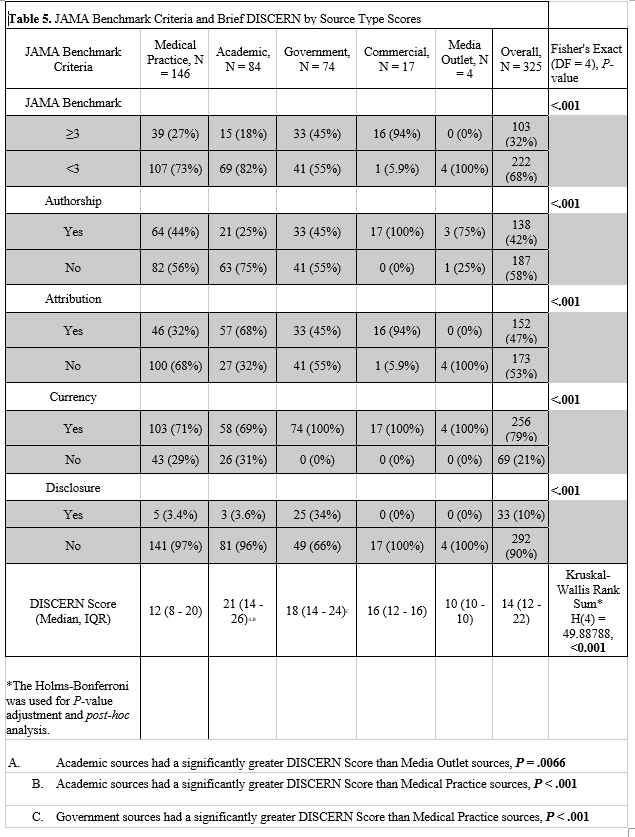

Information Transparency

One hundred three (of 325, 31.7%) sources met 3 or more of the JAMA benchmark criteria. The majority of these sources were Medical Practices (39/103, 37.9%), followed by Government (33/103, 32.0%), Commercial (16/103, 15.5%), Academic (15/103, 14.6%), and Media Outlets (0/103, 0%). Over half of the Medical Practices (82/146, 56%), Academic (63/83, 75%), and Government (41/74, 55%) failed to report authorship in included sources. Completing three or more JAMA benchmark criteria by source type was statistically significant (P= <0.001). Further, there were statistically significant differences in the completion of each JAMA benchmark criterion among source types; complete results are presented in Table 5.

Information Quality

The overall median Brief DISCERN score for cholecystitis FAQs was 14 (12-22). Academic sources presented the highest median scores at 21 out of 30, followed by government sources with 18, commercial sources with 16, medical practices with 12, and media outlets with 10. The Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a statistically significant difference in Brief DISCERN scores among the 5 source types (H(4) = 49.88788, P<0.001 ). Post hoc study of the ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in the median Brief DISCERN scores for Academic sources compared to Media Outlets (P <0.0066) and Medical Practices (P <0.001); as well as Government sources compared to Medical Practices (P <0.001). Academic, government, and commercial sources scored a median score above 16, displaying quality information. All sources may be seen in Table 5.

Discussion

With the high prevalence of cholecystitis, it is deduced that patients are seeking answers online before visiting their physician. Google’s search analytics can be openly accessed to gauge the interest people have in illnesses like cholecystitis, which can then inform physicians and health administrators. The mission of this study was to distinguish the FAQs about cholecystitis and appraise the quality and transparency of sources provided as answers to patients.

FAQs

Our study shows that the most common questions patients seem to be googling on their cholecystitis are fact-based questions accounting for over two-thirds of all the FAQs. Of these fact-based questions, patients seem to be most interested in the recovery time for the treatment of cholecystitis, followed by disease processes. This could be explained by the sudden onset of acute cholecystitis symptoms and by laparoscopic cholecystectomy being an outpatient procedure.1,37 What stuck out the most is that zero of these fact-based questions had to do with cost. This could be due to the relatively lower cost of cholecystectomy procedures covered by Medicare and Medicaid.38–41 These findings would suggest most people are not worried about the cost of cholecystitis treatment, but more so about how long they need to take to fully recover and what it is that is causing their abdominal pain.

Of the policy-based questions, patients were split nearly half and half between wanting to know the indications for treatment options and the complications of treatment options. The definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis is a cholecystectomy.7 Patients may be concerned about having surgery in general, looking for other pain management options; and perhaps, what complications may develop if they do not have surgery.

Valued-based questions made up the smallest amount of the FAQs. Of these value-based questions, more than half were concerned with the success rates of treatment options. We also found that of all the FAQs, 58% were pertaining to surgery. Patients seem not to be as interested in the evaluation of which surgical option is the best. This may be partially explained as the preferred approach for cholecystectomy is laparoscopically, displaying low conversion rates to open and high satisfaction rates post-operatively.42-44 We recommend that physicians emphasize covering the most popular FAQs pertaining to recovery time, management of symptom pain, and the best treatment option including laparoscopy.

Sources

In evaluating the information transparency of our data sample, we report that over two-thirds of all sources scored less than at least 3 or more of the JAMA benchmark criteria, failing to meet benchmark standards. Medical practices accounted for the highest amount of FAQs unable to meet the JAMA benchmark. Academic and government sources also had a majority of articles not meet the benchmark. This result seems to be seen with medical practices in previous Google FAQ studies in a variety of diseases, with academic and government sources showing mixed results.18–21 To our surprise, nearly all of the commercial sources met or exceeded the JAMA benchmark. However, they composed only a small portion of our sample. We recommend physicians who create online information consider the JAMA benchmark to increase their transparency.

Academic, government, and commercial sources were shown to have good quality scores on the Brief DISCERN tool, with academics being the highest scorer. The threshold for good quality (16) on the Brief DISCERN tool was not met with medical practices and media outlets; media outlets being the lowest scorer. However, only four media outlets were found in this study. The trend of medical practices having low-quality scores on the Brief DISCERN tool is a trend that has been reported in previous Google FAQ studies and confirmed in this study.18–21 Medical practices were shown to perform the worst, on average, in the second and sixth questions (Table 4.) of the Brief DISCERN tool. While medical practices could improve on all areas of the Brief DISCERN tool, the second question, which measures the dates of publishing for references, shares a similar measurement of the JAMA benchmark and could be a useful report to increase scores on both scales. Medical practices only need to make a few changes, according to the JAMA benchmark and Brief DICERN, to increase their quality and transparency. This could be a potential advantage for medical practices over the competition and other higher-scoring sources such as academics and government, making their source the preferred recommendation.

Limitations

Our study is limited first by the fact that Google’s variability in its outputs, in general, may affect the reproducibility of our study. With new searches for cholecystitis happening every day on the internet, the generalizability of our study is limited as new FAQs will appear and Google’s top recommendations may shift from one source to another. Another improvement could be to focus on more questions about other cholecystitis treatment plans and their necessity in a follow-up study. The JAMA Benchmark and the Brief DISCERN were used to assess quality and transparency; however, they cannot be used to assess accuracy. This would require a source-by-source comparison which is beyond the scope of our study. These guidelines also do not have a minimum number of references needed; thus, a source could theoretically meet the criteria for both JAMA and Brief DISCERN with just one single reference. Last, categorizing FAQs and answer sources is limited by its subjectivity, allowing for potential overlap between categories.

Conclusion

Most patients turn to the internet for questions pertaining to cholecystitis surgical treatment, information on the disease, and recovery times. Medical practices are the most frequent source of information Google recommends for cholecystitis FAQs but deliver the lowest quality and transparency. We recommend that online sources reform their online information by including the date, author, and references to improve the level of transparency and quality of online information.

Funding/Support: The authors received no funding for this work.

COI/Disclosure: No financial or other sources of support were provided during the development of this protocol. Matt Vassar reports grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Office of Research Integrity, and Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology, all outside the present work.

Acknowledgements: None.

References

1. Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute Cholecystitis: A Review. JAMA 2022; 327: 965–975.

2. Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology 2002; 122: 1500–1511.

3. Telfer S, Fenyö G, Holt PR, et al. Acute abdominal pain in patients over 50 years of age. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1988; 144: 47–50.

4. Eskelinen M. Diagnostic approaches in acute cholecystitis; a prospective study of 1333 patients with acute abdominal pain. Theor Surg 1993; 8: 15–20.

5. Brewer BJ, Golden GT, Hitch DC, et al. Abdominal pain. An analysis of 1,000 consecutive cases in a University Hospital emergency room. Am J Surg 1976; 131: 219–223.

6. CM Vollmer. Treatment of acute calculous cholecystitis. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), Wolters Kluwer 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-acute-calculous-cholecystitis (accessed 18 August 2023).

7. Indar AA, Beckingham IJ. Acute cholecystitis. BMJ 2002; 325: 639–643.

8. Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 2618–2624.

9. Bussey LG, Sillence E. The role of internet resources in health decision-making: a qualitative study. Digit Health 2019; 5: 2055207619888073.

10. Ryan A, Wilson S. Internet healthcare: do self-diagnosis sites do more harm than good? Expert Opin Drug Saf 2008; 7: 227–229.

11. Fraval A, Ming Chong Y, Holcdorf D, et al. Internet use by orthopaedic outpatients - current trends and practices. Australas Med J 2012; 5: 633–638.

12. Jellison SS, Bibens M, Checketts J, et al. Using Google Trends to assess global public interest in osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 2018; 38: 2133–2136.

13. Flanagan R, Kuo B, Staller K. Utilizing Google Trends to Assess Worldwide Interest in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Commonly Associated Treatments. Dig Dis Sci 2021; 66: 814–822.

14. Shah P. [rank for People also ask]: Infinite questions Google PAA handbook. outranking.io, https://www.outranking.io/people-also-ask-handbook/ (2021, accessed 18 August 2023).

15. Shen TS, Driscoll DA, Islam W, et al. Modern Internet Search Analytics and Total Joint Arthroplasty: What Are Patients Asking and Reading Online? J Arthroplasty 2021; 36: 1224–1231.

16. Sullivan B, Platt B, Joiner J, et al. An Investigation of Google Searches for Knee Osteoarthritis and Stem Cell Therapy: What are Patients Searching Online? HSS J 2022; 18: 485–489.

17. Ottwell RL, Shepard S, Sajjadi NB. Central protocol FAQ, https://osf.io/nu3yg/ (2021, accessed 18 August 2023).

18. Shepard S, Sajjadi NB, Checketts JX, et al. Examining the Public’s Most Frequently Asked Questions About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Appraising Online Information About Treatment. Hand 2022; 15589447221142895.

19. Sajjadi NB, Ottwell R, Shepard S, et al. Assessing the United States’ most frequently asked questions about osteopathic medicine, osteopathic education, and osteopathic manipulative treatment. J Osteopath Med 2022; 122: 219–227.

20. Sajjadi NB, Shepard S, Ottwell R, et al. Examining the Public’s Most Frequently Asked Questions Regarding COVID-19 Vaccines Using Search Engine Analytics in the United States: Observational Study. JMIR Infodemiology 2021; 1: e28740.

21. Phelps CR, Shepard S, Hughes G, et al. Insights Into Patients Questions Over Bunion Treatments: A Google Study. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics 2023; 8: 24730114231198837.

22. Google, http://google.com (accessed 2 July 2023).

23. SEO Minion, https://seominion.com/ (accessed 2 July 2023).

24. Starman JS, Gettys FK, Capo JA, et al. Quality and content of Internet-based information for ten common orthopaedic sports medicine diagnoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 1612–1618.

25. Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to Health Questions: Internet Search Results Versus Online Health Community Responses. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e95.

26. Rothwell JD. Mindtap speech, 1 term (6 months) printed access card for rothwell’s in mixed company: Communicating in small groups, 9th. 9th ed. Wadsworth Publishing, 2015.

27. Cassidy JT, Baker JF. Orthopaedic Patient Information on the World Wide Web: An Essential Review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98: 325–338.

28. Kartal A, Kebudi A. Evaluation of the Reliability, Utility, and Quality of Information Used in Total Extraperitoneal Procedure for Inguinal Hernia Repair Videos Shared on WebSurg. Cureus 2019; 11: e5566.

29. Corcelles R, Daigle CR, Talamas HR, et al. Assessment of the quality of Internet information on sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11: 539–544.

30. Cuan-Baltazar JY, Muñoz-Perez MJ, Robledo-Vega C, et al. Misinformation of COVID-19 on the Internet: Infodemiology Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020; 6: e18444.

31. Fan KS, Ghani SA, Machairas N, et al. COVID-19 prevention and treatment information on the internet: a systematic analysis and quality assessment. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e040487.

32. Haragan AF, Zuwiala CA, Himes KP. Online Information About Periviable Birth: Quality Assessment. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2019; 2: e12524.

33. Azer SA, AlOlayan TI, AlGhamdi MA, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: An evaluation of health information on the internet. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 1676–1696.

34. Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, et al. Brief DISCERN, six questions for the evaluation of evidence-based content of health-related websites. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 77: 33–37.

35. Banasiak NC, Meadows-Oliver M. Evaluating asthma websites using the Brief DISCERN instrument. J Asthma Allergy 2017; 10: 191–196.

36. Zheluk A, Maddock J. Plausibility of Using a Checklist With YouTube to Facilitate the Discovery of Acute Low Back Pain Self-Management Content: Exploratory Study. JMIR Form Res 2020; 4: e23366.

37. Lillemoe KD, Lin JW, Talamini MA, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a ‘true’ outpatient procedure: initial experience in 130 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3: 44–49.

38. Procedure Price Lookup for outpatient services: Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy with exploration of common duct, https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup/cost/47564/ (accessed 12 August 2023).

39. Procedure Price Lookup for outpatient services: Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy with cholangiography, https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup/cost/47563/ (accessed 12 August 2023).

40. Procedure Price Lookup for outpatient services: Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy, https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup/cost/47562/ (accessed 12 August 2023).

41. Costs: Medicare, https://www.medicare.gov/basics/costs/medicare-costs (accessed 12 August 2023).

42. Sakpal SV, Bindra SS, Chamberlain RS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy conversion rates two decades later. JSLS 2010; 14: 476–483.

43. Walter K. Acute Cholecystitis. JAMA 2022; 327: 1514–1514.

44. Saber A, Hokkam EN. Operative outcome and patient satisfaction in early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Minim Invasive Surg 2014; 2014: 162643.