Enhancing Investigative Interviewing through the Application of Emotional Intelligence Skills

James D. Hess, Ed.D., OSU School of Healthcare Administration, OSU Center for Health Sciences

Ronald Thrasher, Ph.D., OSU School of Forensic Sciences, OSU Center for Health Sciences

Abstract

Context: Investigating interviewing has both human and technical components. Emotional intelligence is best defined as the ability to perceive an expression emotion, assimilate emotion in thought, comprehend and reason with emotion, recognize emotion in others and regulate one’s own emotions.1 The skills associated with emotional intelligence may be learned and applied to improve the quality and effectiveness of investigative interviewing, thereby increasing the performance of investigators and policing organizations. The purpose of this paper is to identify approaches to the application of emotional intelligence to the investigative interviewing process. These approaches are designed to instruct and aid investigators in the utilization of emotional intelligence skills to improve investigative interviewing skills.

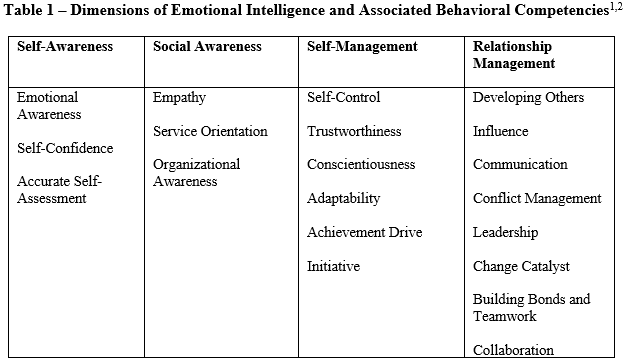

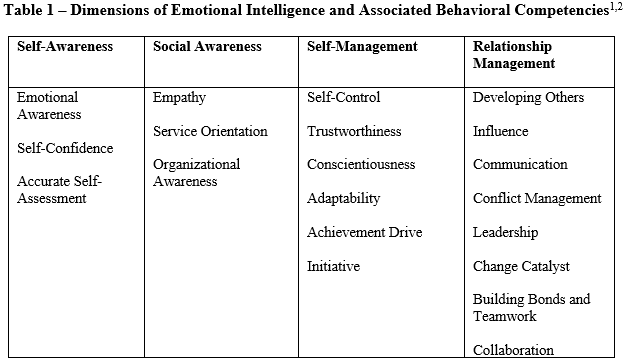

Methods: Goleman’s and Boyatzis’ et al. four essential elements of emotional intelligence and their associated 20 behavioral competencies are utilized to develop a methodology for the application of emotional intelligence skills to investigative interviewing.1,2 A series of questions and observations are outlined to improve emotional intelligence awareness and enhance the utilization of emotional intelligence skills in interviewing processes.

Results: Criminal investigative organizations and investigators may benefit from the development and utilization of behaviors attributed to emotional intelligence, and the application of emotional intelligence skills can enhance investigative interviewing skills and outcomes.

Introduction

A significant amount of effort in the criminal investigation process is devoted to interviewing victims, witnesses and suspects and as a result, a great deal of literature has been generated surrounding the interviewing topic. Interestingly, much of the literature developed around the interviewing discipline focuses more on process and methodology rather than the emotional aspects of the interaction or the attributes of the interviewer. The emotional intelligence level of investigative interviewers is one of the heretofore neglected areas of study.

Emotional intelligence has been best described as the ability to recognize one’s own emotions, as well as the emotion of others, and the ability to manage emotions to positively impact relationships.1,2 Emotional intelligence has been the subject of a significant amount of literature over the past two decades, ranging from debate over whether emotional intelligence is innate or learned, to the categorization of specific behaviors that define emotional intelligence. However, little if any literature has been contributed to how the behaviors associated with emotional intelligence may be applied to enhance investigative interviewing or to interviewing in general. The application of emotional intelligence in the interview setting is the ability to perceive, understand and utilize not only the emotions of the person interviewed but of the interviewer themselves. The purpose of this paper is to review relevant emotional intelligence literature and to identify approaches to the application of emotional intelligence skills to the investigative interviewing process. The paper will present background and rationale for the application of emotional intelligence skills followed by a series of interrogatories and observations demonstrating the application of these skills to investigative interviewing.

Methods

Goleman’s and Boyatzis’ et al. four essential elements of emotional intelligence and their associated 20 behavioral competencies were utilized to develop a methodology for the application of emotional intelligence skills to investigative interviewing.1,2 A series of questions and observations are outlined to improve emotional intelligence awareness and enhance the utilization of emotional intelligence skills in the investigative interviewing processes.

Results

The application of emotional intelligence skills and behaviors can enhance not only the outcome of an individual interview but also the investigative processes associated with positive case outcomes. The ability to assess the potential emotional outcomes and reactions of different interviewing methods can empower investigative interviewers to predict and adapt to interview scenarios, thereby increasing the probability of a more positive case outcome.

Discussion

The discussion will initially focus on the challenges associated with investigative interviewing followed by the methods by which emotional intelligence skills may enhance the interviewing process. Numerous authors have emphasized the importance of interviewing in the investigative process. Evans and Webb commented “the investigative task is the core aspect of policing today and what emerges from that core task is the key element of the ability to interview.”3 Accentuating this point, Williams noted that up to 90 percent of an investigator’s time is engaged in gathering, sorting and evaluating information.4 Providing further support for the importance of interviewing, Einspahr concluded that “solid interviewing skills stand as the cornerstone in law enforcement’s arsenal of crime-fighting weapons.”5 While the importance of interviewing skills is underscored in the literature, some authors note that those skills may be lacking in investigative agencies. Specifically, Euale and Turtle concluded the collecting of information from suspects and witnesses was perhaps the most valuable and yet most elusive policing skill.6

The literature in general reveals that the quality of an investigation is directly correlated to the quality of the interviews conducted. For example, Maguire reported that one of the most critical components of both general and major investigations is a heavy reliance on interview evidence.7 Similarly, the famous ‘Miranda’ decision in the U.S. described the interview room as “the nerve centre of crime detection.”8 Yet in some instances officers are failing to fully discern the importance of every interviewing opportunity. Clarke and Milne, as well as Bull and Cherryman, noted that officers were not discerning the value of utilizing proper interviewing techniques on witnesses and victims, focusing more heavily on the interviewing of suspects of crimes.9,10 According to Yeschke and Maguire, interviewing suspects appear to possess higher status than interviewing witnesses for two primary reasons: 1) because it is viewed as more difficult, and 2) because of the value placed on a confession.11,7 The first of these reasons is not well supported in the literature. A large proportion of suspects willingly and readily make admissions, with research showing percentages ranging from 42 percent to 68 percent.10,12,13,14,15 Addressing the second proposition, many officers perceive suspect interviews as more important since obtaining a confession is the best possible result.16 Some investigators view the suspect confession as a short cut to a conviction and others may perceive the confession as a means of conserving resources.14,17

The information gathering process to develop testimonial evidence is most often an oral exercise and subsequently recorded in the form of a written statement. However, Daniell and McLean found that significant information was lost between the interview and written statement.18,19 Both Milne and Shaw and Milne and Bull concluded that this loss of information was an influencing factor in wrongful acquittals.20,21

While some researchers have offered that individual officers seem more naturally able to obtain detailed information from witnesses and suspects, the majority of officers are challenged in this exercise.22,23 Other researchers report that with the appropriate instruction, most officers can become effective interviewers.24,25,26,27,28 On the whole, research suggests that without the benefit of proper training most police officers are destined to be poor interviewers.21 This lack of effectiveness begs the question of why some investigators are better interviewers than others. Perhaps those interviewers who obtain better results are exhibiting behaviors that cause interviewees to provide more and better information.

With respect to interviewing techniques, one of the most comprehensive programs is the PEACE process, adopted by the police service of England and Wales in 1993.29 The PEACE process is based on the conceptual phases of the interviewing process: 1) Planning and preparation; 2) Engaging with the interviewee and explaining the process; 3) obtaining an Account of the incident; 4) Closure of the interview; and 5) Evaluation of the interview and the interviewer.30 PEACE training was widely adopted in England and Wales with differing levels of training. While the initial evaluation of the PEACE implementation was positive, a subsequent study conducted by Walsh and Milne concluded that 75% of PEACE trained investigators performed no better than those who were not trained.29,31 This led Clarke et al. to make the insightful observation that PEACE training alone may not improve interviewing skills, opening the door for discussion of other factors which may aid in the interviewing process.32

One such factor is the development of rapport. Without developing rapport through the engagement process, officers miss opportunities to appropriately connect with the interviewee, leading to unsatisfactory interview outcomes.33 Ironically, research on the social and interpersonal dynamics of investigative interviewing is lacking.34 Some authors noted the discipline of interviewing could be enhanced through a deeper understanding of the relationship between social influence and rapport, particularly in multiparty interactions.34 As early as 1993, many individual officers had taken the initiative to better understand the psychological and social processes associated with interviewing.35

Further addressing the social/psychological aspects of the interview process, the literature also provides guidance on the attributes of a good interviewer. Yeschke noted that good interviewers exhibit self-awareness and self-confidence, as well as purpose, vision and dedication.11 Swanson et al. reported that a good interviewer is able to convey appropriate emotional responses at various times as needed (e.g., sympathy, anger, fear and joy); is impartial, flexible and open minded; and knows how to use psychology, salesmanship, and dramatics.36 Wicklander and Zulawski set out a more structured profile of a successful interviewer, indicating one should be: objective, polite, eventempered, sincere, interested and understanding.37 Regardless of the terminology used, all of these authors describe the behaviors attributed to emotional intelligence as attributes of a successful interviewer.

Relevant Emotional Intelligence Research

The definition of emotional intelligence and the context in which the term should be used has been a matter of debate in the literature for a number of years.38 The term “emotional intelligence” was first used in the United States in a doctoral dissertation studying the acknowledgement and effects of emotion.39 This work was followed by an emotional intelligence model described by Salovey and Mayer, articulating that emotions could enhance rationality and individuals would be better served to work with, rather than against, their emotions.40 Bradberry and Greaves noted emotional intelligence skills, when considered cumulatively, were vital in representing mental and behavioral functions of individuals beyond their native intelligence.41

The bulk of the literature in emotional intelligence may be encapsulated in the description of three models: 1) ability model; 2) trait model and 3) mixed model.42,43,44 The ability model as described by Salovey and Grewal posited that individuals have varied abilities to process and react to emotional circumstances and as a result develop adaptive behaviors to deal with social situations.42 The trait model proposed by Petrides et al. was based upon the premise emotional intelligence represents a cluster of self perceptions operating at the lower levels of personality.43 Because this model focused on behaviors operating at the subconscious level, it relied heavily on self-measurement and as such was more resistant to scientific calibration.43 The mixed model was best characterized by Goleman’s description of emotional intelligence as a wide array of competencies and skills driving leadership performance.44 Goleman’s model was based on the premise emotional competencies are not innate traits, but rather learned skills that may be developed and improved.44 Since Goleman’s initial work, other researchers have applied his learned behavior model to other areas beyond leadership.44,45,46,47,48

Goleman’s original work on emotional intelligence described the following essential elements or abilities: 1) knowing one’s emotions; 2) managing emotions; 3) motivating oneself; 4) recognizing emotions in others and 5) handling relationships.44 Goleman’s theory of emotional intelligence and its characteristic behaviors has been further refined to include both individual and organizational behaviors and outcomes.1 The fully developed emotional intelligence model as described by Goleman and Boyatzis et al. refined the original five elements into four dimensions and further subdivided these characteristics into 20 behavioral competencies as outlined in the following table.1,2

Applying Emotional Intelligence Skills to Investigative Interviewing

While much of the literature has focused on the theoretical aspects of emotional intelligence, a significant gap exists in the application of these skills to investigative interviewing. Recall that Clarke et al. observed that PEACE training alone may not improve interviewing skills.32 Coupled with the conclusions of Abbe and Brandon that research on the social and interpersonal dynamics of investigative interviewing is lacking, it seems logical that emotional intelligence might play an important role in the interviewing process.34

Successful investigative interviewing requires making a connection with the person being interviewed.33,34 The quantity and quality of information is improved when the interviewee has developed a relationship bond with the investigator conducting the interview, explaining why some individuals are better investigative interviewers than others. It is the authors’ contention the application of emotional intelligence behaviors to the investigative interviewing setting can be learned and replicated to increase the overall effectiveness of investigators as well as the interviewing process. Supporting this notion, the application and learning of emotional intelligence competencies has been previously documented in the literature in the disciplines of problem solving, innovation, decision making and resilience.45,46,47,48

Self-Awareness…Evaluating the Role of the Investigative Interviewer

Applying the emotional intelligence skill of self-awareness and its representative competencies of accurate self-assessment and self-confidence to the investigative interviewing process enables the interviewer to determine his or her appropriate role in the interviewing process.1,2 These skills can enable investigative interviewers to assess their own skills in comparison to others. In instances where there is a choice on the assignment of an investigator, emotional intelligence skills could create a decision path to determine the most appropriate person to plan, design and implement the best interview strategy. Often “case ownership” can be a barrier to honest self-awareness and self-assessment. Without emotional intelligence, investigative interviewers and/or supervisors of investigators fail the first and most important decision, which is “who is the best investigative interviewer for this particular case?”

Application of Self-Awareness Skills to Investigative Interviewing

Given that applying self-awareness skills to investigative interviewing situations is a process that can be learned, the following questions, observations and action steps can serve as a practical guide for utilizing self-awareness skills in investigative interviewing circumstances.

1) Is the investigative interviewer aware of his or her interviewing skills and styles? The emotionally intelligent investigative interviewer will make an honest self-assessment of skills and styles, noting the differences in his or her behaviors and abilities as compared to others. In conjunction with the planning and preparation stages of the PEACE process, self-awareness enables the investigator to foresee how their investigative style might play out in the interview. For example, an investigator might evaluate whether their style has been effective in previous settings in gaining additional information from witnesses or suspects or conversely, whether it has been a hindrance to that process. Additionally, applying the self-awareness competency allows investigators to observe and evaluate the styles of other skilled interviewers to create or modify their own style and effective skill set. The truly emotionally intelligent investigator can push ego issues aside and make accurate self-assessments that are in the best interests of the case and/or team.

2) Would others describe the investigative interviewer as inclusive or exclusive in interviewing processes? While an investigative interviewer may describe himself or herself as more participatory, the more critical aspect is the perception of others, particularly those who will ultimately evaluate the effectiveness of the interview. Inclusive may mean asking the opinions of others in the planning and preparation phase regarding appropriate interview technique(s). In other cases it may mean including others in the actual interview itself. Inclusion is particularly important when interviewing witnesses from a vulnerable population, i.e. children, elderly or emotionally challenged individuals. The emotional intelligence competency to be exercised here is being self-aware enough to know when to include others in the planning and/or engagement process.

3) Is the investigative interviewer confident in his or her interviewing skills? Utilizing the planning and preparation components of the PEACE interviewing methodology can aid the interviewer in exuding self-confidence in interview situations by anticipating potential answers or denials and developing additional follow up questions.30 Being self-confident also implies having the courage to acknowledge one’s weaknesses in the interviewing process. Ede and Shepherd noted that many investigators enter the interview with assumptions, expectations and hypotheses about the event they are investigating.17 Difficulties arise when interviewers approach the interview with unfounded or erroneous assessments of the incident in question.25 An emotionally intelligent interviewer is both self-aware and self-confident enough to recognize biases and minimizes them to the greatest extent possible.

4) Does the interviewer have a tendency to reach first to deploy emotion in the interviewing setting, or conversely, to rely more on rational analysis? Understanding one’s natural style will enable the interviewer to better focus on the appropriate interviewing method. For example, in cases where emotions may be escalating due to the nature of the crime, interviewers will be better served to concentrate on rationality and pragmatism as a means of offsetting natural emotional responses.

5) Given the human tendency to avoid areas of perceived weakness, can the interviewer identify the most uncomfortable aspects of the investigative interviewing process and strive to spend more time in that domain in order to dispel the discomfort? For example, Clarke et al. determined that the closure phase of many interviews was poorly conducted.32 The application of the self-awareness and self-confidence competencies to this circumstance would imply that the interviewer would recognize this as a weakness and develop an improvement strategy to remediate the weakness.

Social Awareness…Assessing Impacts and Consequences

Applying the emotional intelligence attribute of social awareness and its core competencies of empathy (caring for others), service orientation and organizational awareness to investigative interviewing enables interviewers to appropriately judge the impact of their interviewing techniques on witnesses and suspects as well as other investigators who may be involved in the interview.1,2 The best investigative interviewing methods are those that can be understood and successfully replicated by other investigators to generate positive case outcomes. The organizational environment and supervisory attitudes are pivotal to this process. Clarke et al. concluded that supervision and interviewer evaluation were integral to the success of interviewing policy and remains a challenge for most policing agencies.32

Individuals who practice the emotional intelligence behavior of empathy can visualize the impact of their actions before they are taken.1 In the investigative interview setting, this requires that the interviewer foresee the reaction of witnesses, complainants or suspects to tactics employed by the interviewer. Additionally, exhibiting empathy by being aware of the witness’s or suspect’s culture, values and morés will enable the investigative interviewer to make a more rational judgment regarding the best interviewing techniques, as well as the overall process by which interviews are conducted.

Application of Social Awareness Skills to Investigative Interviewing

In assessing and developing social awareness skills, investigative interviewers should consider the following questions, practical observations and action steps.

1) Who and what will be most affected by the outcome of a particular interview? The PEACE model function of planning and preparation focuses primarily on the development of strategies for the conduct of the interview.31 This function can be augmented and enhanced through the application of the emotional intelligence skill of social awareness by contemplating the impact and consequences of the interview before it is conducted. This emotional intelligence skill requires the investigative interviewer to play out scenarios of interview outcomes to determine both their short and long-term consequences and effects. From a practical application perspective, the interviewer should contemplate during the planning phase possible impacts and consequences of a particular interview strategy on other interviews or contemplated actions. Weighing these impacts and consequences may alter an interview strategy.

2) In circumstances where a case is being handled by a team, to what extent should others on the investigative team who might be impacted by the outcome of the interview be involved in the interview planning? The skill of social awareness includes the skill of scanning the environment to determine if and when inclusion or exclusion is necessary or appropriate. When contemplating a particular interview scenario, it is critical to determine whether others on the investigative team might be impacted by the utilization of an interview technique or how information gained might impact the direction of the investigation. This consideration is particularly important when an investigation is being coordinated with multiple investigative authorities and/or when special or vulnerable interviewees are being questioned. While most often these questions are contemplated after an interview is completed, investigators have the opportunity to move more quickly if outcome scenarios are discussed with fellow team members in advance of an interview. Such methods also strengthen the investigative team environment by building trust bonds among team members.

3) What investigative interviewing techniques are most appropriate given the culture and/or values of the interviewee? Being socially aware requires the investigative interviewer to assess the historical and cultural morés of the interviewee to determine appropriate actions. For example, if the culture of the witness or suspect precludes females from talking to males one on one, then a female interviewer may be more effective. Specifically, race, gender, religious affiliation and nationality must be thoughtful considerations in the pre-planning of interviewing scenarios. Likewise, those same factors must be weighed and considered in determining who on the investigative team is best suited for a particular interview setting or assignment.

4) In recalling an investigative interview that resulted in undesirable outcomes, can the interviewer reflect on the negative consequences experienced, thereby providing an opening to identify how the interview situation could have been executed?

5) Can the interviewer identify a particular interview setting that was inconsistent with the values and culture of the policing organization and note the values that were violated? Investigative interviewers can benefit by determining how the interview could have been handled to be more consistent with the values and culture of the organization.

Self Management…Managing Emotions in the Interview Process

Self-management and its components of self-control, trustworthiness, conscientiousness, adaptability, achievement drive and initiative described by Goleman and Boyatzis et al. are arguably the most important emotional intelligence skills for investigative interviewers.1,2 Additionally, in order for an investigative interviewer to gain moral authority in any case setting, he or she must first be viewed as trustworthy by others directly or indirectly involved in the case, i.e. witnesses, complainants and cooperating agencies. Investigative interviewers can utilize self-management skills to establish a consistent record of achievement, while simultaneously earning trust from fellow investigators, victims and/or witnesses.

In settings where the speed at which a case can be resolved is highly valued, the temptation is to avoid the use of interviewing techniques which occupy valuable time. For example, Williamson reported a negative attitude toward quick interrogation-type questioning due to the fact that this method resulted in less information being revealed.35 Clarke and Milne found that in many cases witnesses and/or victims were not being interviewed, rather the focus was on taking a statement in a question/answer format.9 Clarke and Milne and Milne and Bull both acknowledge that the utilization of cognitive interviewing skills (following a structured format of establishing rapport, receiving an uninterrupted account of events and determining if events can be recalled out of order), while time consuming, is still more likely to generate increased information.9,49

The emotional intelligence behavior of conscientiousness can be invaluable to the investigative interviewer. Clarke et al. reported that even though investigators had been trained on the importance of interview closure, this aspect of the PEACE model was not optimally employed.32 This failure might be due to a lack of time; however, self-management through disciplined conscientiousness is perhaps the best means of addressing this issue. Clarke et al. also noted that conscientiousness demonstrated by supervisors in evaluating interviewers had some positive impact on interviewer performance.32

The adaptability function of emotional intelligence, while not specifically described as such, has some history in the interviewing literature. Clarke and Milne reported that the use of cognitive interviewing or conversation management was limited even after PEACE training.9 The emotional intelligence skill of adaptability is especially applicable in the Account phase of the PEACE model. Use of cognitive interviewing and conversation management techniques require the interviewer to adapt to the responses of the interviewee. While many of the informational responses might be anticipated during the Planning and Preparation phase, there are circumstances where an interview can move in directions that were not anticipated. Shepherd described the ideal interviewer as one who can convey a range of emotions as well as empathy and sincerity whenever necessary.50 Interviewers who possess the competency of adaptability can respond quickly and smoothly to changes in interview direction, thereby eliciting additional information and perspective.

Application of Self-Management Skills to Investigative Interviewing

The following interrogatories and observations will enable investigative interviewers to establish or more fully develop their self-management emotional intelligence skill set.

1) Is the investigative interviewer merely focused on his or her pursuits or are they truly interested in achieving the best interview and case results? Emotionally intelligent investigative interviewers are characterized by their ability to suppress their ego for the best possible case outcome. This might require consulting another more experienced interviewer for guidance or allowing another interviewer to take the lead in a particular interview setting. The attribute of self-management allows the interviewer to not be concerned about who gets the credit for case closure, but rather that the case is resolved with the best possible outcome for the victim.

2) Is the investigative interviewer focusing too much on the desire for a speedy result? Bazerman and Malhotra noted that time pressures often lead to bad judgments.51 Walsh and Milne noted that investigators who had undergone PEACE training tended to conduct longer interviews and were able to get interviewees to talk more freely.31 In interview circumstances where the witness, victim or suspect is less than forthcoming, cognitive interviewing or conversation management may elicit more and better information.49 These practices, while requiring more patience, are also more likely to generate the best possible interview outcome.

3) How may an interviewing process be utilized to build trust with the witness, victim and/or suspect? Mayer and Caruso noted that individuals high in emotional intelligence are able to build real social fabric, i.e. trust and respect, with those with whom they interact.52 Abbe and Brandon identified a number of influences that can affect the interviewer/interviewee interaction, including positivity, credibility and shared understanding.34 Accordingly, emotionally intelligent investigative interviewing processes are those that can build trust with the interviewee by establishing rapport, credibility and a shared understanding of interview goals. This is of course somewhat limited by the fact that in the case of suspects, goals are often contradictory. However, in the case of victims and witnesses, trust can be paramount in eliciting information.

Complex cases resulting in negative consequences will be more readily accepted by those impacted if they trust the case was revolved consistent with the values of the organization and the community it serves. Exemplary of this point is the development of the PEACE process. Clarke et al. noted that the PEACE process was initiated in response to a number of miscarriages of justice and resulted in a more ethical approach to interviewing individuals suspected of committing a crime.32 Clarke et al. also noted that the implementation of the PEACE process had a profound effect on the legal and procedural issues (outlining of legal rights) of interviewing.32 Thus it can be argued that the development of the PEACE process was itself an act of trust-building within the community.

4) Is the investigative interviewer willing to adapt to new investigative interviewing techniques rather than relying upon the entrenched processes of the past? Walsh and Milne noted that training alone will not lead to increased performance levels in interviewing, implying that other approaches will be necessary to increase performance.31 When the need for a new or specialized investigative interviewing process or technique arises, those who can self-manage and adapt to new techniques or processes may be more likely to experience success in the interviewing process. From an emotional intelligence perspective, the honest acknowledgement of a need to break with the practices of the past is critical to building self-confidence, as well as developing the relationships necessary to affect a positive solution result. 53

5) Is the investigative interviewer willing to quickly admit to and correct misjudgments? No other self-management characteristic is as important in the development of emotional intelligence behaviors as the ability to openly admit to mistakes.9,13,21 Mistakes make emotionally intelligent human beings stronger and give them the opportunity to truly connect with others in honesty and humility. However, the ability to admit mistakes or shortcomings can be problematic among police personnel. Indeed, Milne and Bull suggested that police cultures often prevent officers from recognizing their interviewing deficiencies or admitting they are less than confident.21 This is consistent with Baldwin’s findings that police officers are generally poor at evaluating their own interviewing abilities.13 Thus it is important for interviewers to have assistance in the evaluation process. Accordingly, Clarke and Milne concluded that interview quality was enhanced when an interview supervision policy was present in the workplace.9

6) To remain consistent with the evaluation phase of the PEACE process, can investigative interviewers and their supervisors to recall and assess both the interview process as well as the methods employed? Did the interviewer accomplish their aims? Did the processes utilized increase or decrease the level of trust with witnesses and/or victims. Should others have been involved in the investigative interviewing process and if so, how? It is also helpful here to identify what actions could have been taken to develop the interviewing skills of someone else. In replaying a scenario when an investigative interviewer failed to acknowledge and correct a misjudgment, what consequences or impacts did that failure cause? How could the scenario have played out differently if the mistake had openly acknowledged and corrected?

Relationship Management…Relating to Others in the Investigative Interviewing Process

As noted previously in Table 1, relationship management includes developing others, influence, communications, conflict management, leadership, change catalyst, building bonds and teamwork.1,2 The success of investigative interviews is dependent upon the interviewer’s ability to effectively plan for and communicate desired interview outcomes, facilitate accurate victim/witness accounts and manage potential conflicts. In interviewing processes, the ability to manage relationships can be a critical factor to a successful interview outcome. Even the best of interview plans can have unintended results if not properly communicated, including the proper articulation of the interviewing processes. Walsh and Milne noted mediocre performance in explaining the purpose of the interview and establishing rapport with the interviewee.31 The establishment of rapport is a relationship management process and requires a great deal more than a mechanical interaction. In instances where investigators revert back to poor interviewing habits, supervisors should be called upon to remediate through the evaluation process. However, bringing about fundamental change in an interviewer’s style can be fraught with potential conflict. The ability to manage the evaluation process and its associated potential conflict is central to the supervisory process, requiring supervisors/evaluators to exercise emotional skills while simultaneously attempting to steer necessary changes.

Application of Relationship Management Skills to Investigative Interviewing

Conflict, communication and relationship management are all inextricably linked to the investigative interviewing and case-solving process. Investigative interviewers should consider the following questions and actions in the effort to more fully develop the relationship management skill set.

1) Given that rapport is an integral part of investigative interviewing, each phase of the process (from planning to evaluation) should be viewed as a means of developing or furthering relationships with victims, witnesses, fellow officers and supervisors. Relationships are based upon communication and trust, and the emotionally intelligent investigator looks at every interviewing circumstance as an opportunity to develop or improve the relationship with another person.

2) In those instances where other officers or coordinating agencies are involved in an investigation, how does the investigative interviewer communicate with those individuals or agencies? This aspect of relationship management requires a regular and consistent method of communication that reinforces the role of each person involved in the investigation. Likewise, relationship management is critical in the supervisory and evaluation domain. Supervisors of interviewers should be direct and compassionate in their communications of process improvement. The benefits of the supervisory/evaluation process can be negated by poor and/or less than positive communication methods. In instances when an interview has been delegated to another party, it remains critical to support that delegation in all communications.

3) Are communications in conflict situations regarding investigative interviewing direct and forthright? Emotional intelligence is exhibited in conflict settings by seeking first to understand the position and feelings of the other person.52 Clarke and Milne and Walsh and Milne noted that interviewers often failed to completely explore a suspect’s motivation for an admitted criminal act.32,31 Thus in investigative interviewing, the emotionally intelligent interviewer listens more than they speak and seeks opportunities to learn as much as possible during the interview setting. The application of this emotional intelligence competency is also supported by the use of conversation management and cognitive interviewing techniques. Through this interactive communication process, it is possible that information can be gained to solve other cases unrelated to the current interview. Periodically, investigators and/or their supervisors may disagree on how a particular interview should be handled. In such instances being direct about conflicting views is important to demonstrate honesty, and exhibiting compassion in moments of tension develops the trust necessary to foster long-term relationships.

4) What are the investigative interviewer’s attributes in managing conflict? Huy concluded that the emotionally intelligent individual manages volatility by expressing compassion while exhibiting and furthering the values of the organization.53 This requires one to acknowledge and examine one’s own emotions in moments of conflict. In the interview setting this principle is appropriately applied when an interviewee’s response(s) create an emotional response in the interviewer. This can easily happen in cases involving vulnerable victims or extremely violent crimes. The emotionally intelligent response in these circumstances is to acknowledge and manage one’s emotions so as to maintain control over the interview process. This skill can enable interviewers to build and maintain rapport even in instances where expressing compassion for the suspect is extremely challenging.

5) While reflecting on an investigative interviewing solution that created a large amount of conflict or raised one’s emotions, interviewers should recall the methods used to communicate during the interview. How could the process have been handled to lessen the conflict or controversy? How could one’s emotional responses have been better controlled or managed through the planning, engagement or account processes. When appropriate, on a case-by-case basis, it may be worthwhile to identify those who may have been negatively impacted (witnesses, other officers or supervisors), and inquire of those individuals how the process should have been handled from their perspective. This action takes a great deal of moral courage but will pay large dividends in the development of better interviewing skills, as well as case management in the future.

Conclusion

Every investigator and criminal investigative organization share the goal of enhancing the quality of investigative interviewing, and the application of emotional intelligence skills can assist in the attainment of that goal. Investigative interviewers who are self-aware and can accurately and honestly assess their interviewing strengths in comparison to others in the organization have the advantage of leveraging the attributes of others in the interviewing process. The ability to assess the potential emotional outcomes and reactions of different interviewing methods can empower investigative interviewers to predict and adapt to interview scenarios, thereby increasing the probability of a more positive case outcome. The process of building and maintaining relationships with both victims and witnesses is inherently human which requires an emotional perspective and while time consuming, can generate better interview outcomes. Additionally, interview settings have the potential of generating conflict, and the ability to manage that conflict involves an emotional intelligence skill that can determine the ultimate success of the case-solving process. Finally, the application of emotional intelligence skills and behaviors can enhance not only the outcome of an individual interview but also the investigative processes associated with positive case outcomes.

There are a number of criticisms that may be leveled at these propositions. Ostensibly there is little, if any, literature on the topic of applying emotional intelligence competencies to the investigative interviewing process. Given this limitation, additional research into this discipline might focus on testing individual investigators to determine levels of emotional intelligence and correlating those assessments with case clearing rates, criminal admission rates and/or interview evaluation scores.

References

1. Goleman, D. Emotional intelligence: perspectives on a theory of performance. In: C. Chermiss and D. Goleman (eds.). The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2001.

2. Boyatzis, R., Goleman, D., and Rhee, K.. Clustering competence in emotional intelligence: insights from the emotional competence inventory (ECI). In: R. Bar-On and J.D.A. Parker (eds.). Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000.

3. Evans, G. and Webb, M. High profile - but not that high profile: interviewing of young persons. In: E. Shepherd (ed). Aspects of Police Interviewing. Leicester: British Psychological Society; 1993.

4. Williams, J.W. Interrogating justice: a critical analysis of the police interrogation and its role in the criminal justice process. Canadian Journal of Criminology. 2000;42(2):209-240.

5. Einspahr, O. The Interview Challenge: Mike Simmen versus the FBI. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2000;69 (4):16-20.

6. Euale, J. and Turtle, J. Interviewing and Investigation. Canada: Emond Montgomery Publications; 1998.

7. Maguire, M. Criminal investigation and crime control. In: T. Newburn (ed) Handbook of Policing. Cullompton: Willan Publishing; 2003.

8. Miranda v. Arizona. 384 U.S. 436, 1966:501.

9. Clarke, C. and Milne, R. National evaluation of the PEACE investigative interviewing course. (Report No. PRSA/149). London: Home Office; 2001.

10. Bull, R. and Cherryman, J. Helping to identify skills gaps in specialist investigative interviewing: Literature review. London: Home Office; 1995.

11. Yeschke, C.L. The Art of Investigative Interviewing - A Human Approach to Testimonial Evidence (2nd ed). Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2003.

12. McConville, M., Sanders, A. and Leng, R. The case for the prosecution: police suspects and the construction of criminality. London: Routledge; 1991.

13. Baldwin, J. Video-taping of police interviews with suspects - an evaluation. (Police Research Series: Paper No.1). London: Home Office; 1992.

14. Moston, S., Stephenson, G. and Williamson, T. (1992). The effects of case characteristics on suspect behaviour during police questioning. British Journal of Criminology. 1992;32:23-40.

15. Cherryman, J. and Bull, R. Reflections on investigative interviewing. In: F. Leishman, B. Loveday, & S. Savage, (Eds.) Core Issues in Policing (2nd ed). London: Longman; 2000.

16. Stockdale, J.E. Management and supervision of police interviews. Police Research Group. Home Office: London; 1993.

17. Ede, R. and Shepherd, E. Active Defence (2nd ed). London: Law Society Publishing; 2000.

18. Daniell, C. The truth – The whole truth and nothing but the truth? An analysis of witness interviews and statements. Unpublished dissertation. University of Plymouth; 1999.

19. McLean, M. Quality investigation? Police interviewing of witnesses. Medicine, Science and the Law. 1995;35:116-122.

20. Milne, R. and Shaw, G. Obtaining witness statements: Best practice and proposals for innovation. Medicine, Science and the Law. 1999;39:127-138.

21. Milne, R. and Bull, R. Investigative Interviewing: Psychology and Practice. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 1999.

22. Shepherd, E. and Kite, F. Teach ‘em to talk. Policing. 1989;5:33-47.

23. Morgan, C. Focused Interviewing. Canada: Trafford Publishing; 1999.

24. Gudjonsson, G. The Psychology of Interrogations, Confessions and Testimony. Chichester: Wiley; 1992.

25. Baldwin, J. Police interrogation: what are the rules of the game? In: D. Morgan and G. Stephenson (Eds) Suspicion and Silence: The Right to Silence in Criminal Investigations. London: Blackstone; 1994.

26. Memon, A., Milne, R., Holley, A., Bull, R. and Koehnken, G. (1994). Towards understanding the effects of interviewer training in evaluating the cognitive interview. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1994;8:641-659.

27. Williamson, T. From interrogation to investigative interviewing: strategic trends in police questioning. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology.1994;89-99.

28. Ord, B., Shaw, G. and Green, T. Investigative Interviewing Explained. LexisNexis Australia: Butterworths; 2004.

29. McGurk, B.J., Carr, M.J. and McGurk, D. Investigative Interviewing Courses for Police Officers: An Evaluation. (Police Research Series: Paper No.4). London: Home Office; 1993.

30. Milne, B., Shaw, G., and Bull, R. Investigative interviewing: The role of research. In: Carson, D., Milne, Pakes, F., Shalev, K., and Shawyer, A. (eds.). Applying Psychology to Criminal Justice. Chichester: Wiley; 2007:65-80.

31. Walsh, D. and Milne, R. Keeping the Peace? A study of investigative interviewing practices in the public sector. Legal and Criminal Psychology. 2008;13(1):39-57.

32. Clarke, C., Milne, R., and Bull, R. Interviewing suspects of crime: The impact of PEACE training, supervision and the presence of a legal advisor. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 2011;8(2):149-162.

33. Walsh, D. and Bull, R. Examining rapport in investigative interviews with suspects: Does its building and maintenance work? Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. 2012;27(1):73-84.

34. Abbe, A. and Brandon, S. E. The role of rapport in investigative interviewing: A review. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 2013;10(3):237-249.

35. Williamson, T. Review and prospect. In Eric Shepherd (ed) Aspects of police interviewing. Issues in Criminological and Legal Psychology. 1993;18:57-59.

36. Swanson, C.R., Chamelin, N.C. and Territo, L. Criminal Investigation. United States: McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2002.

37. Wicklander, D.E. and Zulawski, D.E. Interview and Interrogation Techniques - A Training Course. Illinois:Wicklander - Zulawski and Associates, Inc.; 2003.

38. Mayer, J.D., Salovey, P. and Caruso, D.R. Emotional intelligence: new ability or eclectic traits. American Psychologist. 2008;63(6):503-517.

39. Payne, W.L. A study of emotion: developing emotional intelligence; self integration; relating to fear, pain and desire. Dissertation Abstracts International. University microfilms No. AAC 8605928. 1985; 47:203A.

40. Salovey, P. and Mayer, J. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 1990;9:185-211.

41. Bradberry, T. and Greaves, J. The Emotional Intelligence Quickbook. San Diego, California: Talentsmart; 2003.

42. Salovey, P. and Grewal, D. The science of emotional intelligence. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:281-285.

43. Petrides, K.V., Pita, R. and Kokkinaki, F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology. 2007;98:273-289.

44. Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence. New York, New York: Bantam Books; 1995.

45. Hess, J.D. and Bacigalupo, A.C. Enhancing decisions and decision-making processes through the application of emotional intelligence skills. Management Decision. 2011;49(5):710-721.

46. Hess, J. D. Enhancing innovation processes through the application of emotional Intelligence skills. Review Pub Administration Manag. 2014:2 (143):2.

47. Hess, J.D. and Bacigalupo, A.C. Enhancing management problem-solving processes through the application of emotional intelligence skills. Journal of Management. 2014:2(3):1-17.

48. Hess, J.D. and Benjamin, B.A. Utilizing emotional intelligence skills to enhance leadership and resilience-building processes. Journal of Global Economics, Management and Business Research. 2015;2(3):113-128.

49. Milne, R. and Bull, R. Interviewing by the police. In: D. Carson and R. Bull (eds). Handbook of Psychology in Legal Contexts. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 2003.

50. Shepherd, E. Ethical interviewing. Policing. 1991;7(1):42-60.

51. Bazerman, M. and Malhorta, D. It’s not intuitive: strategies for negotiating more rationally. Negotiation. 2006;9(5).

52. Mayer, J, and Caruso, D. The effective leader: understanding and applying emotional intelligence. Ivey Business Journal. November-December (Reprint # 9B02TF10). 2002:1-5.

53. Huy, Quy N. Emotional capability, emotional intelligence and radical change. Academy of Management Review. 1999;24(2):325-345.